Optimizing Multimodal Fusion: Selective Parameter Merging between Vision-Language and Language Models

Key Findings

We’ve been diving deep into the world of model fusion lately, and I’m excited to share some fascinating discoveries about combining Vision-Language Models (VLMs) with traditional Language Models (LLMs).

It turns out that throwing all parameters together isn’t the way to go! Our experiments revealed that a more thoughtful, selective approach yields dramatically better results. The winning strategy? Preserve the VLM’s original embedding layers while only merging the self-attention mechanisms. This actually makes intuitive sense when you think about how these models process visual information.

Even more interesting is how the optimal merging strategy changes as you move through the network. Early layers work best when they stay close to the VLM’s original parameters, while deeper layers can incorporate more of the LLM’s language capabilities. This progressive approach consistently beat uniform merging strategies across all our benchmarks.

Background: Model Fusion in Multimodal Systems

When a VLM and LLM share the same base architecture (like Qwen2.5-VL-7B and Qwen2.5-7B-Instruction), they have compatible language processing components that make them perfect candidates for merging. Typically, a VLM consists of a vision encoder plus the LLM architecture, which opens the door to partial parameter merging.

The usual approaches to model merging include parameter averaging, task arithmetic, and adapter fusion. But here’s the thing: these methods often treat all parameters equally or focus narrowly on task-specific adaptation. We wanted to try something more nuanced based on how different components of these models actually process multimodal information.

Research Hypotheses

Based on our understanding of how these models work, we came up with two key hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Selective Component Fusion

We thought that merging only self-attention tensors while preserving the VLM’s original embedding tensors would work better than merging everything. Why? Because embedding tensors in the VLM are specifically optimized to handle both text and visual tokens, while the LLM’s embeddings have only ever seen text.

Hypothesis 2: Layer-wise Progressive Merging

We suspected that varying the merging weights across layers would outperform uniform merging. The idea was to give greater influence to the VLM in early layers and more LLM influence in deeper layers. This makes sense because early layers process visual tokens closer to their raw form, while deeper layers work with more abstract representations that might benefit from the LLM’s language understanding.

Experimental Setup

Models and Datasets

- Base VLM: Qwen2.5-VL-7B-Instruct

- Component LLM: Qwen2.5-7B-Instruct

- Evaluation Datasets: MATH-Vision and Math-Visita mini (both involving visual-textual reasoning)

Merging Settings

We compared two different approaches to parameter selection:

- Setting 1: Merging all LLM tensors including embedding tensors, layer norms, and MLPs

- Setting 2: Merging only self-attention tensors in each layer

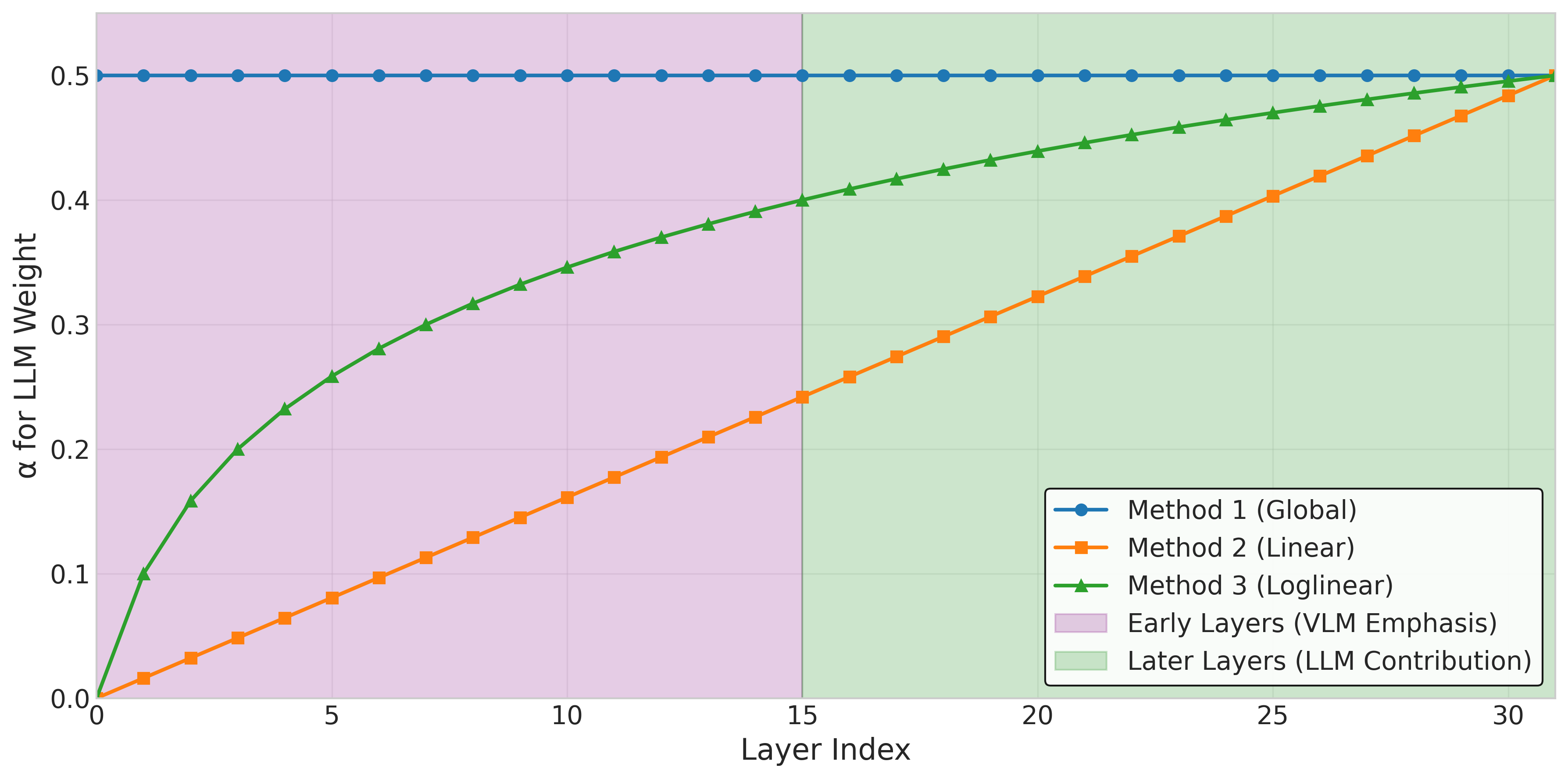

Figure 1: Illustration of the three different weight distribution strategies across model layers. Method 1 applies a constant weight, while Methods 2 and 3 progressively increase LLM influence in deeper layers. (α=0.5)

Figure 1: Illustration of the three different weight distribution strategies across model layers. Method 1 applies a constant weight, while Methods 2 and 3 progressively increase LLM influence in deeper layers. (α=0.5)

Merging Methods

We explored three different strategies for determining the merging weights:

- Method 1: Global Weight Merging - applying a single global weight ratio (α) across all merged parameters

- Method 2: Linear Layer-wise Progressive Merging - linearly increasing the LLM’s influence from early to deeper layers

- Method 3: Loglinear Layer-wise Progressive Merging - increasing the LLM’s influence on a logarithmic scale across layers

Weight Notation

For our experiments, we used a standard interpolation formula for model merging:

(1 - α)θ(VLM) + αθ(LLM) = θ(Merged)

Where α represents the weight given to the LLM parameters:

- α = 0.4: 60% VLM + 40% LLM influence

- α = 0.5: 50% VLM + 50% LLM influence

- α = 0.6: 40% VLM + 60% LLM influence

This formula is applied to the respective tensors being merged. For example, with α = 0.4, each merged tensor is a weighted combination where the original VLM tensor contributes 60% and the LLM tensor contributes 40% to the final value.

Results and Analysis

Overall Performance Comparisons

Our experiments revealed some interesting patterns across different configurations:

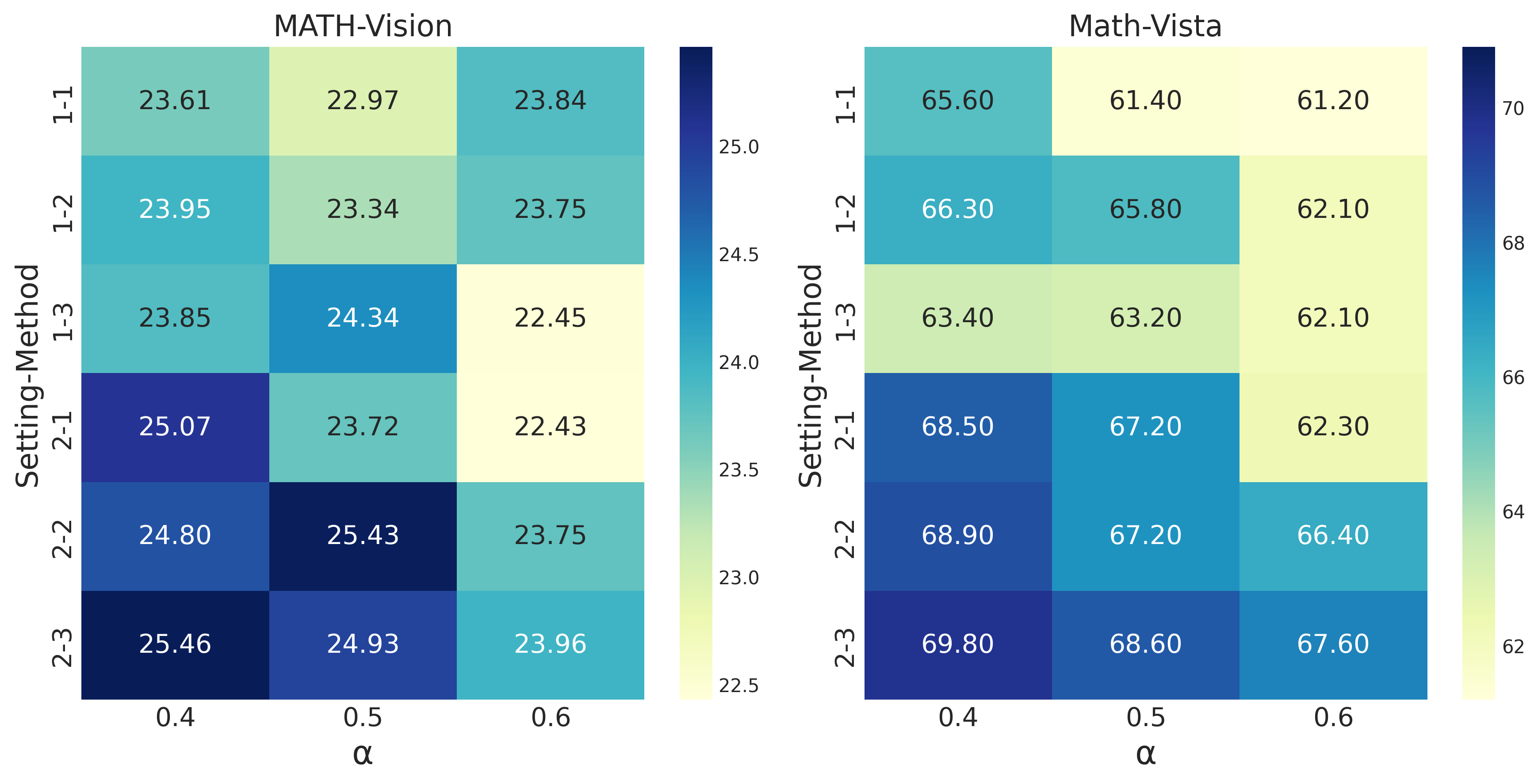

Figure 2: Heatmap visualization of performance across all experimental configurations. The color intensity represents accuracy, with darker blues indicating higher performance.

Figure 2: Heatmap visualization of performance across all experimental configurations. The color intensity represents accuracy, with darker blues indicating higher performance.

Hypothesis 1: Selective Component Fusion

Setting 2 (self-attention only) consistently outperformed Setting 1 (all tensors) across most method and weight combinations. The difference was particularly striking on the Math-Vista mini dataset.

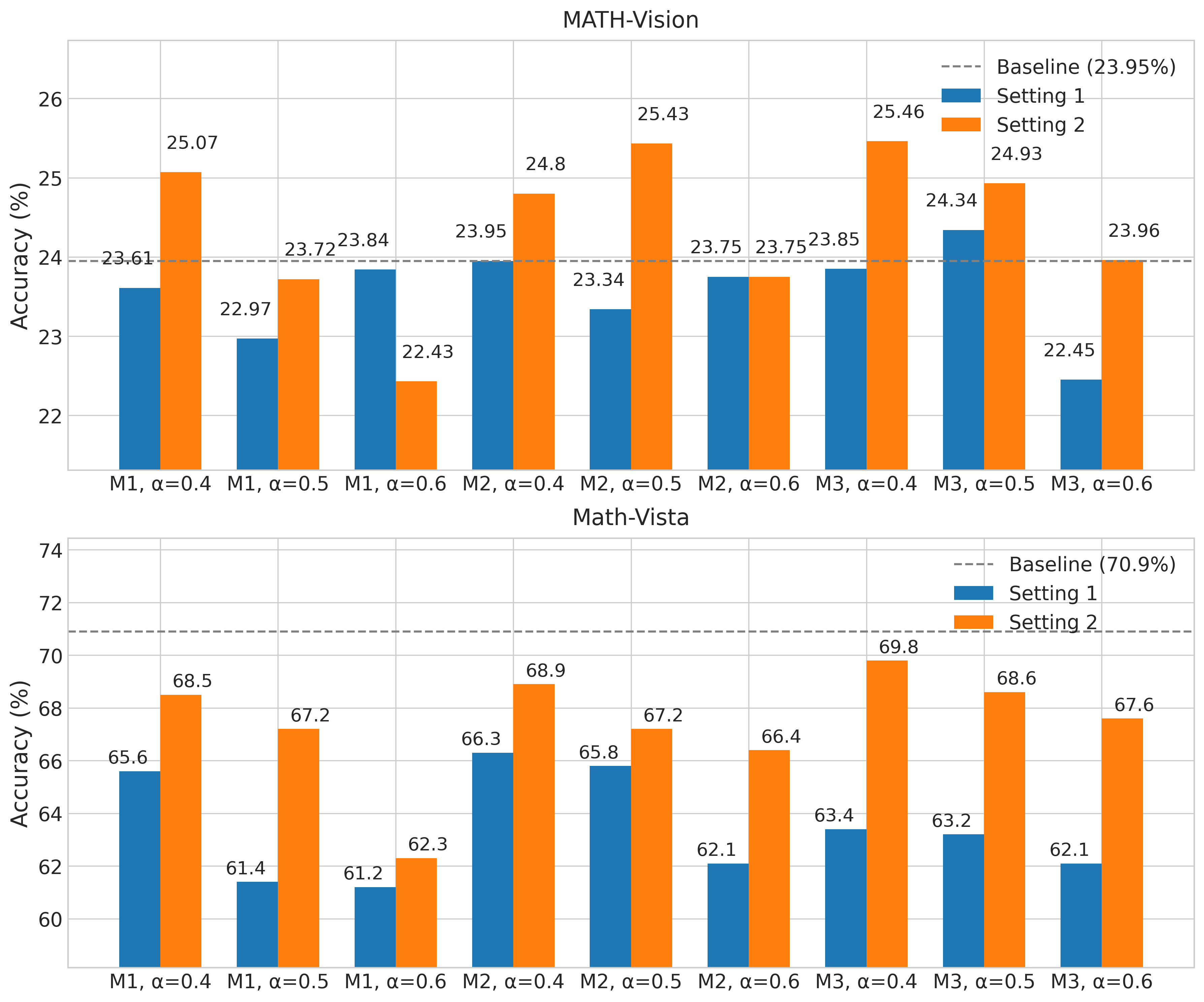

Figure 3: Direct comparison of Setting 1 vs Setting 2 across different method-weight combinations. Setting 2 generally achieves higher accuracy.

Figure 3: Direct comparison of Setting 1 vs Setting 2 across different method-weight combinations. Setting 2 generally achieves higher accuracy.

The improvement becomes even clearer when we look at the direct performance delta:

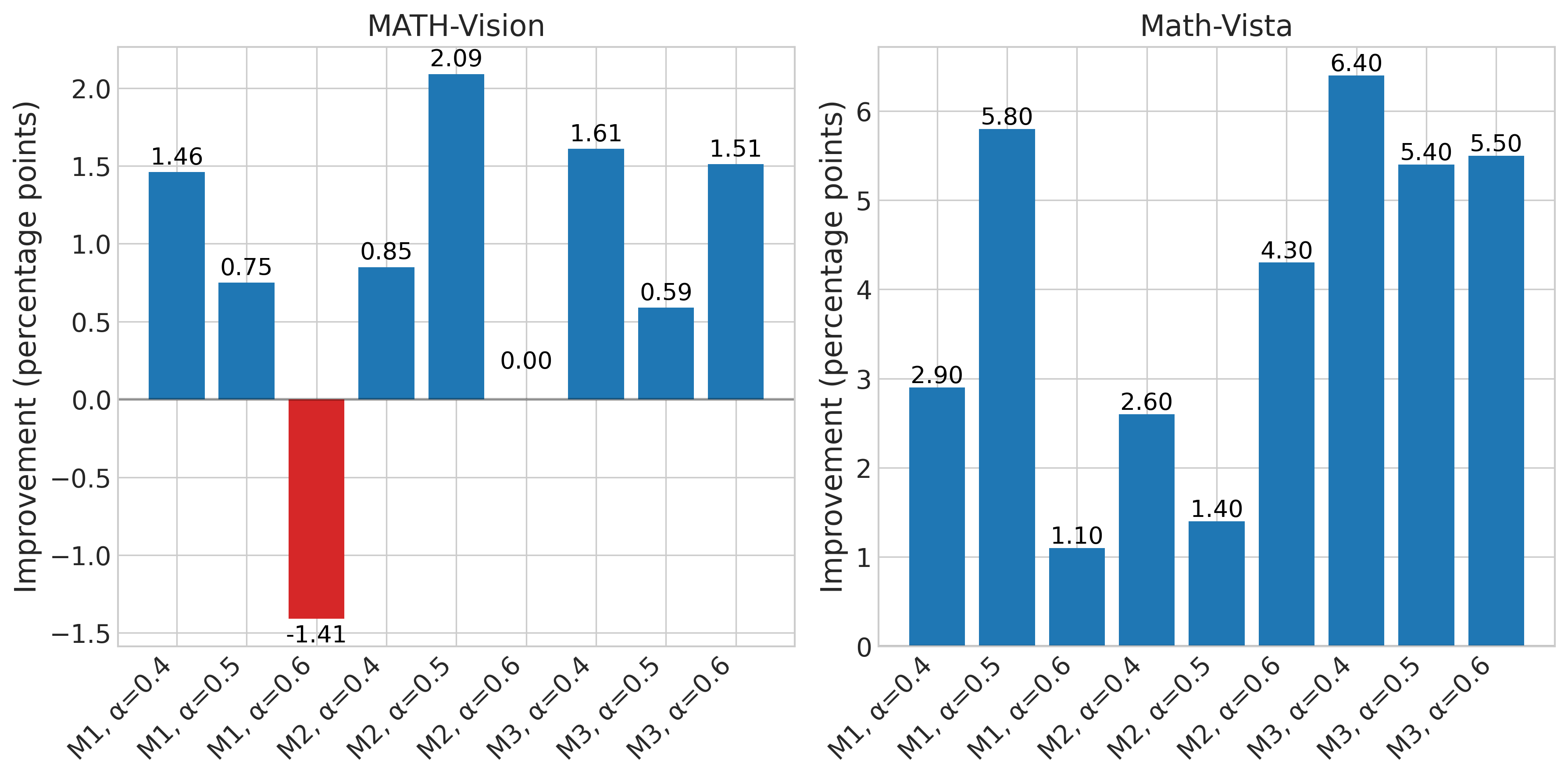

Figure 4: Performance improvement of Setting 2 over Setting 1 for each configuration. Positive values (blue) indicate where Setting 2 outperforms Setting 1.

Figure 4: Performance improvement of Setting 2 over Setting 1 for each configuration. Positive values (blue) indicate where Setting 2 outperforms Setting 1.

As you can see in Figure 4, Setting 2 outperforms Setting 1 in 16 out of 18 comparisons across both datasets. For MATH-V, Setting 2 shows improvements in 7 out of 9 cases with an average improvement of 0.83 percentage points. For Math-Vista mini, the results are even stronger - Setting 2 outperforms Setting 1 in all 9 comparisons with an average gain of 3.93 percentage points.

This strongly supports our first hypothesis that preserving the VLM’s embedding tensors while only merging self-attention components leads to better performance. The improvement is especially notable in tasks that require stronger visual reasoning capabilities, suggesting that preserving those VLM embedding tensors is indeed critical.

Hypothesis 2: Layer-wise Progressive Merging

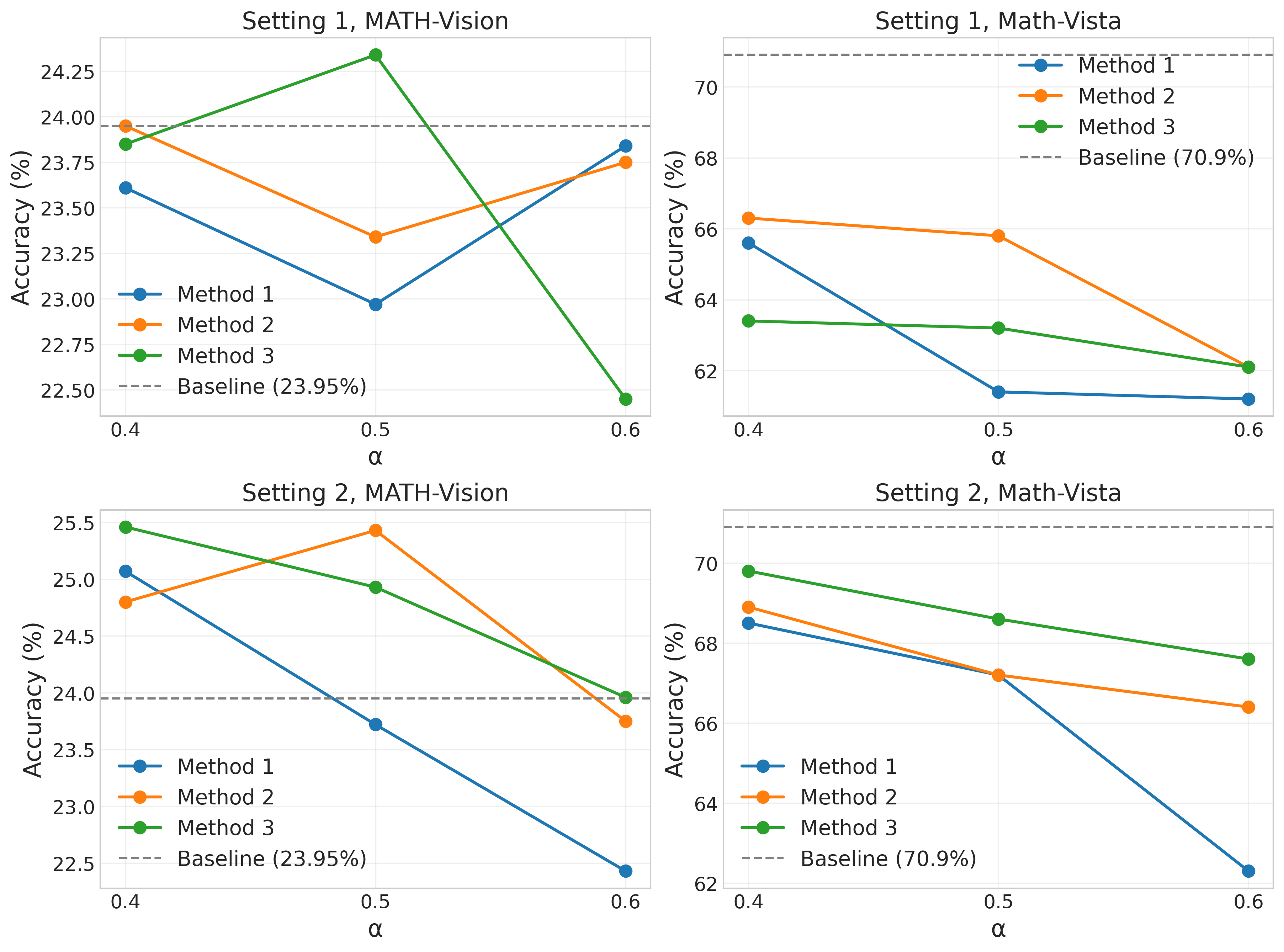

Our second hypothesis predicted that layer-wise increasing methods (Methods 2 and 3) would outperform global weight fusion (Method 1). The results show substantial support for this hypothesis, with a 79.2% success rate across all configurations and datasets:

Figure 5: Performance trends across different weight values for each method. Methods 2 and 3 often outperform Method 1 and show more graceful degradation at higher weights.

Figure 5: Performance trends across different weight values for each method. Methods 2 and 3 often outperform Method 1 and show more graceful degradation at higher weights.

The advantage of layer-wise methods is even more pronounced in Setting 2 (the more effective setting overall), with an 83.3% success rate. This trend is particularly notable at higher LLM weight values (0.5 and 0.6), where Methods 2 and 3 consistently outperform Method 1 across both datasets.

The data reveals three important patterns that support Hypothesis 2:

-

Methods 2 and 3 show better resilience at higher weight values (0.6), degrading more gracefully than Method 1.

-

In Setting 2, Method 3 (loglinear layer-wise) achieves the best overall performance, suggesting that a more gradual introduction of LLM influence in deeper layers is optimal.

-

The layer-wise approaches generally perform better on Math-Vista mini, suggesting they better preserve visual reasoning capabilities when incorporating more LLM influence.

Optimal Weight Balance

Across most methods and settings, a weight value of 0.4 (60% VLM + 40% LLM influence) produces the best results. The best overall configuration is Setting 2, Method 3, with weight 0.4, which achieves:

- 25.46% on MATH-Vision(1.51 points above baseline)

- 69.8% on Math-Vista mini (closest to the baseline of 70.9%)

This confirms that maintaining stronger VLM influence while selectively incorporating LLM capabilities yields optimal performance for multimodal reasoning tasks.

Understanding the Math-Vista Challenge

An intriguing observation is that all fusion configurations underperform the baseline VLM (70.9%) on Math-Vista mini, with the best result (69.8%) still falling short. This suggests that even selective merging may dilute the VLM’s specialized visual processing capabilities, which may be critical for Math-Vista mini’s visual-textual reasoning demands. Incorporating LLM parameters, while beneficial for language abstraction or tasks like MATH-Vision(where we see a 1.51-point gain), might introduce a trade-off that slightly impairs performance on datasets heavily reliant on the VLM’s original vision-language synergy. This highlights a potential limitation of fusion: balancing multimodal improvement against preserving task-specific strengths.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that intelligent, selective parameter merging between VLMs and LLMs can produce better multimodal models than naive merging approaches. Here are the key insights:

-

Embeddings Matter: Preserving the VLM’s embedding tensors is crucial for maintaining the model’s ability to process visual information effectively.

-

Component-Specific Merging: Not all model components benefit equally from fusion; self-attention mechanisms appear to be the most promising candidates for merging.

-

Layer-Dependent Fusion: The optimal merging strategy varies across layers, with early layers benefiting from stronger VLM influence and deeper layers accommodating more LLM contribution.

-

Moderation in Merging: Even in the best-performing configurations, the VLM’s parameters should maintain greater influence (approximately 60%) for optimal multimodal performance.

-

Task-Dependent Effects: The two datasets show different sensitivity patterns to the merging strategies, suggesting that visual reasoning (Math-Vista mini) benefits more consistently from Setting 2 and Methods 2/3 than mathematical reasoning (MATH-V).

Conclusion

What we’ve learned through this exploration of VLM and LLM fusion is pretty eye-opening. It turns out that smashing together models isn’t about brute force—it’s about finesse. The most successful approach we found was selectively merging just the self-attention mechanisms while keeping the VLM’s original embedding layers intact. And the real magic happens when you apply different merging strategies throughout the network’s depth.